In 2015, a group of ten Dutch history students from the University of Groningen gradually found out that their core business – thinking, writing, and telling about continuities and discontinuities – was useful. Indeed, all jokes cast aside, history could be useful. That is to say, these young historians discovered that their discipline, which is often seen as fun but practically irrelevant, could have serious impact. They made this discovery when they wrote a so-called ‘learning history’ of the place-based approach of the local government of Groningen. An assignment during the course ‘Learning History & Organizations’.

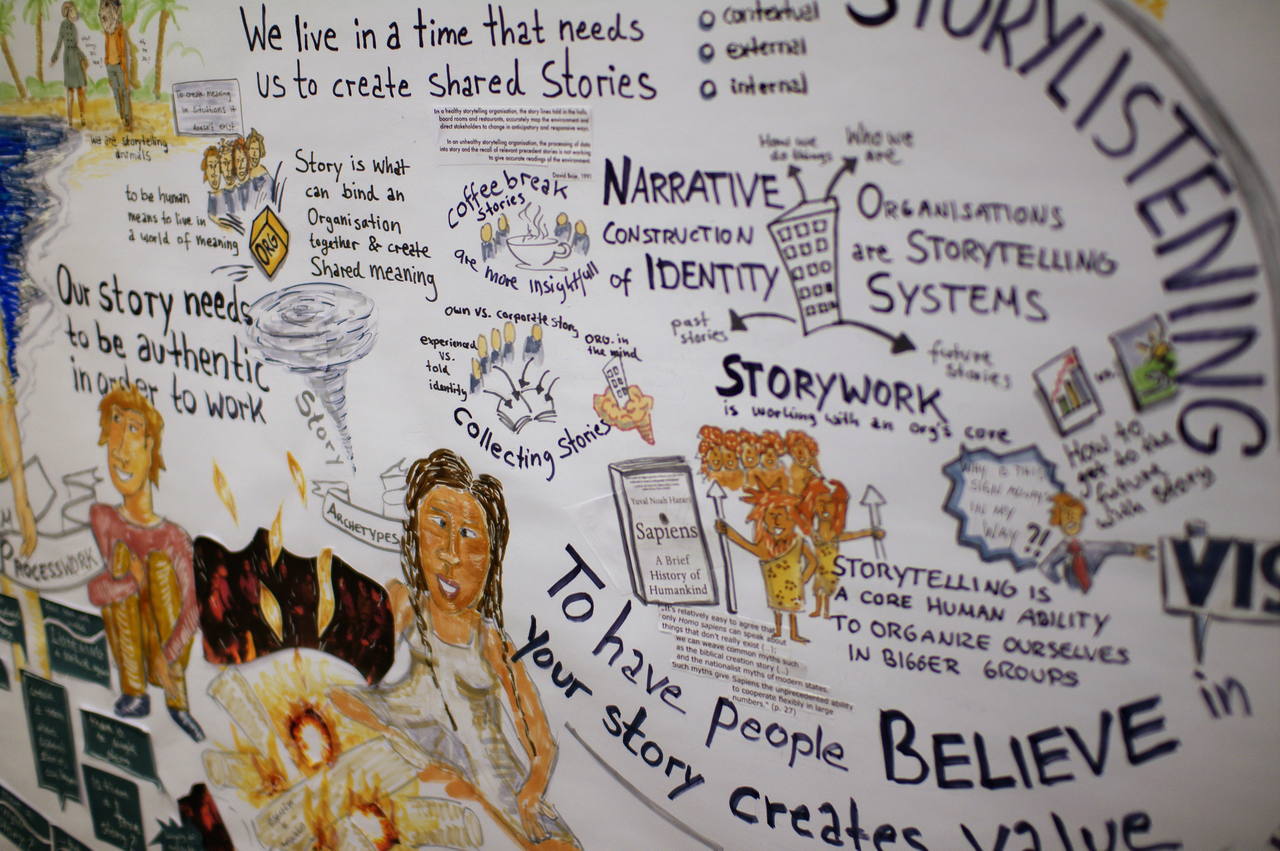

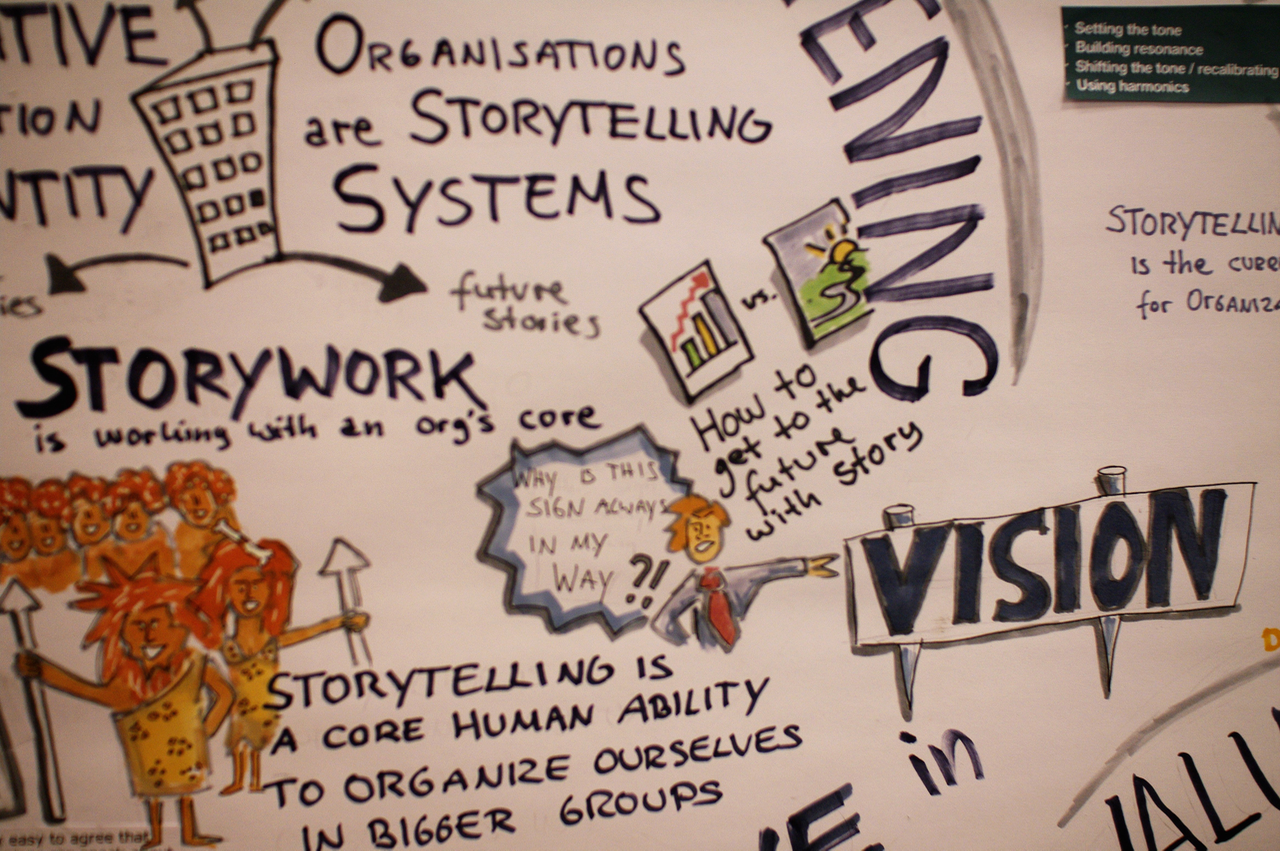

Learning history is a method that enables organizations to learn from their past. Based on a paper trail (various documents, reports, correspondences, etc.) and interviews we write ‘learning histories’. These learning histories then become the basis for dialogues in and between organizations to foster processes of collective learning. The goal, in the Groningen method, is to enable organizations to become ‘learning organizations’, and – even better – systems of organizations to become ‘learning systems’. Groningen, however, is not the only area where this method gains ground. A strongly overlapping method is the storytelling method of Christine Erlach and dr. Karin Thier, which we hoped to further explore during the master class of Christine Erlach at the congress Beyond Storytelling. So we packed our bags and together with dr. Rik Peters travelled to Heidelberg, curious what we would find across the border.

Aside from a lively and historically intruiging city and loads of enthusiastic people passionate about storytelling, we found two splendid additions to our own learning history method: a new interview technique and various effective ways to present the results of these interviews. In order to trace valuable tacit knowledge possessed by employees, Christine interviews employees using an ‘Ereigniskurve’. The Ereigniskurve is a supporting tool with which the employee can visualize his or her experiences on a time scale, and which enables the interviewer to in depthly and accurately interview the employee about these experiences. In addition, and it may sound silly at first, Christine emphasized the importance of truly listening. Whereas we were trained to accurately and actively interview, specifically searching for information based on the paper trail we analyze, Christine claimed the gist is in how people tell their stories – and they have their stories; don’t worry about that.

Christine also taught us new ways of production after the harvest of the interviews. Central to our Groningen learning histories are the experiences from employees, combined with the historical knowledge of the researcher, and presented in a narrative filled with citations and reflective learning questions. However, Christine demonstrated various different ways of presenting the harvest: combining the stories of the employees in one visual ‘roadmap’, in a comic, or as we saw in ‘Augenhöhe project’ from Daniel Trebien, in a film. It is important to stress, though, that the welding of the stories in a format is not the end of the story. In fact, when the format is ready for use the story begins. For the stories have to be shared, through dialogue, within the organization in order that people learn from it.

Eager to blend Christine’s method with our own in our line of work, we gave it a shot in our local government in Groningen. This local government is dealing with a major transformation from the Dutch welfare state to a ‘participation society’, in which many national tasks have been decentralized and another approach in relation to collaboration with civilians is being implemented. A large aspect of this transformation in Groningen is the further development of the so-called ‘place-based approach’; a task for which we have been employed. In short, the place-based approach is a contextual approach in which integral aspects of an area are decisive for governmental policy-making and operationalisation, as opposed to sectoral urban policy.

Right now we are busy interviewing our collegaes and collecting stories. Every interview we start by asking: could you please visualize your professional experience on a scale from positive to negative by drawing a line. This question asks people to think about their professional life in order of a story. They recollect their different experiences – which are stories in themselves – and connect them to each other in a bigger story of their professional experience as a whole. The Ereigniskurve in the form of a line then serves as a guideline for the interview. The next question we ask is if they want to explain the line they drew. From this point onwards the listening begins. Sometimes we interrupt by asking, for example, what they learned from this or that experience. But we try taking the advice from Christine to heart: stop asking, start listening.

We already collected a bunch of beautiful stories. The next step is analyzing all the material and discussing it within the organisation. In analyzing the stories we search for tacit knowledge. That is implicit knowledge of which the owner doesn’t know he or she has. There is not one way for doing this. In the Dutch language we have a saying that you have to ‘read between the lines’ which, in this context, can be used as a metaphor for the method. On presenting and discussing the stories and their hidden knowledge we are thinking of (innovative) ways for doing that. One idea is to present and discuss the stories (whether in a classic presentation in text, a ‘roadmap’ or a comic) in a room which is totally filled with prints of citations from the interviews. In the end this blog is a story of our own learning history in making learning histories and we are somewhere in the middle of it. We ourselves are curious how the story continues…

Rients and Martijn supported us throughout the BEYOND STORYTELLING conference.

Learn more about them on their linkedIn profiles:

https://www.linkedin.com/in/rients-verschoor-7b20624a/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/martijndejp/